The Politics of Persuasion: Strategic Branding in Hungary’s Electoral Landscape

Orbán Was Winning Like a Brand. The Opposition Still Hasn’t Learned How.

This essay explores how political branding has shaped Hungary’s electoral landscape. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s ruling Fidesz–KDNP coalition has secured four consecutive supermajorities by building a clear, emotionally resonant brand centered on belonging, security, and control — executed with long-term strategic discipline. In contrast, the opposition has consistently failed to articulate a shared purpose, identity, or message. Fragmented, reactive, and protest-driven, it has lacked emotional connection and struggled to present a compelling alternative. The result: four decisive victories for the ruling coalition, and four defeats for the opposition. Hungarian voter behavior is driven less by ideology than by emotion. Without strategic brand-building, opposition parties remain ineffective — even as dissatisfaction with Fidesz grows.

Conventional wisdom suggests that leaders must “walk the talk.” My usual contrarian approach is the reverse this time: focus on the talk rather than the walk. In this essay, I deliberately set aside the question of whether the political “product” delivers. Instead, I analyze the communication, the narrative work, and the branding strategies that underpin Fidesz’s dominance.

As a marketer, I know that branding is one of the most effective long-term investments. Strong brands generate superior shareholder returns, wheather crises with resilience, and recover faster. Politics is no different. A brand is not a slogan but a system — multi-layered and strategically constructed. When executed well, it includes:

Brand Core: a clear blueprint and purpose

Brand Identity: coherent architecture and visual design

Brand Positioning: a well-defined market address

Brand Experience: a narrative about how it feels to engage with the brand

Brand Communication: a distinct and consistent voice

Brand Consistency: unified messaging and visuals

Brand Engagement: a strong bond with its community

This essay is therefore not a policy analysis but an exercise in political marketing — focused on branding and brand strategy.

From an objective standpoint, since returning to power in 2010, Orbán’s Fidesz–KDNP coalition has delivered one of the most consistent, strategically disciplined, and impactful political communication campaigns in post-communist Europe — arguably even by Western standards.

From a marketing perspective, the government operated like a high-performance boutique brand: continuously investing in communication, cultivating emotional loyalty, asserting narrative dominance, and shaping public discourse with remarkable discipline.

The opposition, by contrast, has often explained its failures by pointing to government propaganda, media dominance, or the supposed ignorance of voters. While these factors cannot be dismissed entirely, they also serve as convenient excuses that deflect responsibility. The deeper problem is simpler: in marketing terms, the opposition is vastly less professional.

This essay aims to unpack some of the branding layers — particularly in the formative 2010–2015 period — that established Fidesz’s enduring dominance.

Take 1:

Political Marketing Has to Understand the Need States Driving Political Brand Choice

The year 2010 marks a pivotal milestone in Hungarian political marketing. It was when Viktor Orbán and the Fidesz–KDNP coalition won the elections, launching four consecutive supermajorities.

Understanding this “ground zero” moment is crucial to analyzing their success, extracting lessons, and applying them today for the benefit of democracy as a whole.

Ahead of the 2010 national elections, the Hungarian branch of Synovate (now Ipsos), a global marketing research firm, released insights on how political brands were positioned during the national election campaign.

Travelling back to understand this “ground zero” moment, revisiting Synovate’s (now Ipsos) proprietary Censydiam model reveals important insights. The analysis treats political choice not as a rational or ideological decision, but as an emotionally driven act rooted in subconscious motivations.

Unlike consumer goods, political brands are complex constructs made up of people, values, narratives, and cultural signals. Yet, like consumer products, political brands succeed only when they satisfy specific emotional and psychological needs of voters — essentially, political “need states.”

Understading the Censydiam Framework

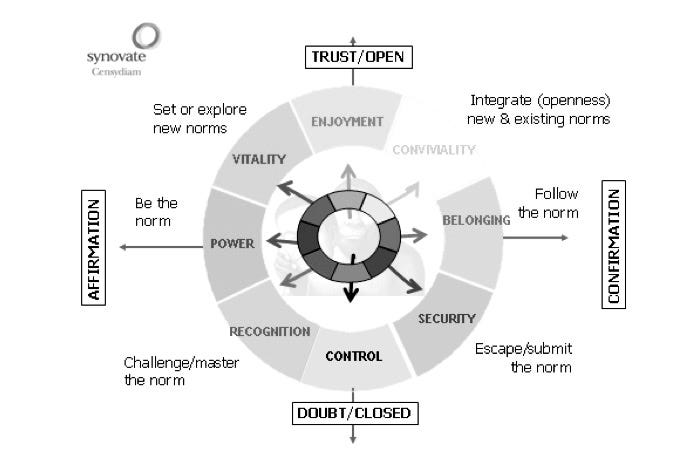

The Censydiam model is built around two axes:

Horizontal: Individualism (self-driven) vs. Collectivism (community-driven)

Vertical: Openness (trust, extroversion) vs. Closedness (doubt, introversion)

These intersecting axes create eight distinct motivational segments, each representing a different psychological driver of brand — or voter — choice:

Because 80% of human behavior is subconscious, voters often choose parties based on what feels right emotionally, rather than stated beliefs.

Therefore people often don’t vote according to what they say they believe, but based on emotional alignment — which parties, brands, or leaders "feel right" to them.

Mapping Political Brands to Motivation Segments

Political ideologies and political brands, the press release argues, are no different —also map to these needs.

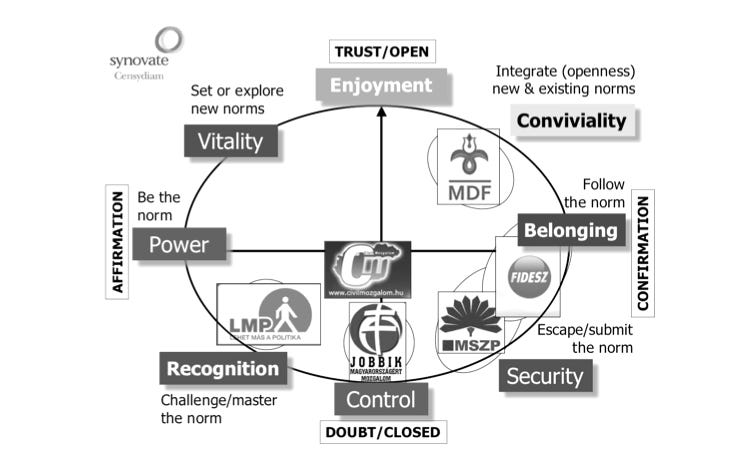

Earlier Synovate (now Ipsos) studies also found that Hungarian voters cluster heavily in the Belonging and Security segments, with a secondary presence in Control. This makes Hungary a voter base that is emotionally drawn to community, protection, and order — more than novelty, prestige, or fun.

Hungarian Political Parties in the 2010 Campaign

Understanding this, successful political parties in Hungary are those who speak directly to these motivations — and those that don’t often fail to connect with voters, regardless of their policy platform. During the 2010 election campaign, the analysis mapped Hungarian political parties based on how their campaign messages and branding aligned with motivational needs.

Jobbik (far-right nationalist): Positioned clearly in the Control segment, emphasizing national self-governance, law and order, with uniforms and disciplined imagery.

LMP (green/liberal): Targeted Recognition, appealing to young urban voters with creative visuals and “being different” messaging.

MDF & Civic Movement: Lacked clear positioning, falling between Enjoyment and Conviviality, leading to electoral irrelevance.

Fidesz–KDNP (center-right): Centered on Belonging (+++) and Security (+), using family-oriented visuals and slogans promoting stability.

MSZP (socialist): Claimed Security (+++) and Belonging (+), but failed to emotionally outcompete Fidesz.

Notably, both mass parties operated in overlapping motivational zones, but Fidesz outperformed by presenting a more trustworthy and emotionally aligned narrative, especially in post-crisis Hungary.

Key Strategic Takeaways from the Press Release

Voter choice is emotional first, ideological second.

Clarity beats complexity: niche parties must own a single motivational space.

Hungary’s dominant voter needs are Belonging, Security, and Control. Successful brands own and reinforce these spaces consistently.

Take 2:

There is a Need for Offering Alternative to Orbán’s Political Brand About Clarity and Control

Since 2010, Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz has established itself as one of Europe’s most effective political brands, excelling across nearly every branding layer during its first two terms.

Fidesz built its dominance by excelling across every major layer of branding — and by venturing into advanced strategic territories.

Brand Core: They articulated a clear mission and emotionally charged purpose. Since 2010, Fidesz has consistently framed itself as the protector of Hungary’s sovereignty, Christian values, and national identity — a unifying vision that resonated across elections.

Brand Identity: They cultivated a stable and recognizable image. Consistent use of national colors, familiar fonts, slogans such as “Hungary is doing better”, and Orbán’s central, CEO-like figure reinforced a coherent political identity.

Brand Positioning: They claimed key emotional territories — Belonging, Security, and Control. By presenting themselves as the party of stability and tradition, in contrast to a fragmented opposition, Fidesz aligned with voter fears and aspirations in uncertain times.

Brand Experience: They staged campaigns as emotional, community-driven spectacles. Large-scale rallies, family-centered visuals, and grassroots events fostered belonging and pride, making political participation feel empowering and communal.

Brand Communication: They mastered simple, emotionally resonant messaging. Narratives like “Stop Brussels”, “Protect our families”, and “Let’s not become like the West” relied on repetition and moral framing to build lasting associations.

Brand Consistency: They reinforced stability through disciplined leadership and centralized control. Orbán’s continued role, long-term communication strategy, and message alignment across all party levels sustained trust and brand strength.

Brand Engagement: They cultivated a strong bond with their community, positioning themselves not just as a political party but as a cultural identity. Like Apple or Nike, Fidesz sells a lifestyle: belonging to the “true Hungary.”

Narrative Expansion: They broadened appeal by selectively adopting left-wing themes such as family subsidies or wage growth, reframed within nationalist rhetoric. This allowed the brand to resonate across social classes while preserving ideological coherence.

Global Positioning: Like a boutique brand, Hungary under Fidesz commands disproportionate global attention. Bold, polarizing messages amplified by international media make the brand larger than its domestic market size.

Brand Risks: The model is not without vulnerabilities. Heavy reliance on fear-based messaging risks voter fatigue; international reputational damage could erode credibility abroad; and without innovation, the brand may stagnate.

Fidesz’s success illustrates how professional, disciplined branding can shape political outcomes over the long term. By systematically building a clear mission, recognizable identity, emotionally resonant positioning, and engaging narratives — while expanding into global attention and lifestyle-based appeal — the party created a brand that transcends ordinary politics. Its dominance is not simply a product of resources or government control, but of sustained, strategic brand management. Understanding these layers helps explain why the opposition has struggled to compete: without comparable brand clarity, coherence, and emotional resonance, even widespread dissatisfaction with the ruling party fails to translate into electoral success.

Take 3:

Regain the Occupied Traditional Left-Wing Spaces or Find New Proprietary Narratives

Part of Orbán’s success comes from strategically occupying emotional spaces traditionally associated with the left:

Utility price cuts framed as protection from foreign corporations.

Family benefits implemented through a nationalist lens.

Anti-globalist rhetoric targeting the EU, George Soros, and multinational corporations.

Worker-centric messaging blending pro-labor rhetoric with nationalist themes.

By appropriating these areas, Fidesz limits the opposition’s ability to claim distinctive, proprietary narratives. For the opposition to regain relevance, they must work harder to identify issues and narratives that genuinely resonate with voters — ones that reflect their values while addressing contemporary concerns.

Take 4:

Missed Opportunities and Weaknesses Define the Opposition’s Brand Void

In stark contrast to Fidesz’s disciplined and emotionally resonant branding, the Hungarian opposition between 2010 and 2025 consistently struggled to construct a coherent political brand. While the ruling party delivered clarity, the opposition projected confusion — reactive, fragmented, and emotionally unanchored. Across seven core branding dimensions, the weaknesses are especially visible:

Brand Core: The opposition lacked a unified purpose or emotional mission. MSZP (Hungarian Socialist Party) drifted between diluted social democracy and short-term populist gestures, while the Democratic Coalition (DK), led by former Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány, focused more on opposing Orbán than presenting a forward-looking national vision. Without a compelling blueprint or shared direction, the opposition’s offer felt like rejection rather than renewal, failing to inspire lasting loyalty.

Brand Identity: Parties repeatedly rebranded into obscurity. Names, logos, slogans, and alliances shifted frequently. LMP gradually lost its distinctiveness, Together 2014 offered little coherence, and Momentum struggled to maintain a singular identity as it expanded. Voters were left unsure who stood for what — or why.

Brand Positioning: Most opposition parties defined themselves primarily as “anti-Fidesz,” rather than clarifying what they stood for. Jobbik’s shift from far-right nationalist to centrist alliance partner blurred ideological lines and alienated its base. MSZP and DK often competed in the same space, undermining collective appeal. Without a clear address in the political market, voters struggled to locate them.

Brand Experience: Opposition events lacked emotional pull. Unlike Fidesz’s large-scale rallies, Momentum’s “NOlimpia” campaign in 2017 was a rare grassroots success. Most other events felt transactional — opportunities to engage were limited, sporadic, and rarely repeatable.

Brand Communication: Messaging was often complex, technocratic, or overly negative. MSZP and DK emphasized policy details and bureaucratic critique, missing the emotional and symbolic language that connects with voters. Social media efforts were inconsistent; Momentum leveraged digital platforms effectively, but in isolation. Overall, opposition communication focused on resistance rather than vision.

Brand Consistency: Frequent leadership changes, shifting alliances, and internal conflicts undermined public trust. Each election cycle brought new logos, new leaders, or new crises, preventing the delivery of a steady, reliable narrative.

Brand Engagement: Opposition presence outside urban centers was limited. Momentum reached younger, educated voters, but broader grassroots networks were weak. The 2022 opposition alliance appeared top-down and disconnected in rural communities, whereas Fidesz maintained local networks and year-round engagement.

The opposition did not fail solely because of Orbán’s strength; it failed because it never built a coherent, emotionally resonant, and strategically disciplined brand. While Fidesz offered voters a mission, identity, and community, the opposition offered only protest and resentment. Slogans like “O1G” express anger but fail to build vision or emotional connection, limiting appeal to moderate or undecided voters.

Unless the opposition addresses this branding deficit — uniting around a shared mission, streamlining its identity, and connecting emotionally with Hungary’s dominant voter needs (Belonging, Security, Control) — it will continue to lose not only elections, but trust.

Take 5:

Opposition Without Vision is Constantly Locked in a Endless Protest Loop

From 1990 to 2010, Hungarian politics was dominated by cycles of protest driven more by voter fatigue than by visionary alternatives.

Today, the opposition risks falling into the same trap. Outrage-driven campaigns, clickbait-style slogans, and aggressive rhetoric — such as the viral O1G hashtag or anti-Orbán memes — may capture attention online and generate likes and shares, but they fail to build credibility, trust, or lasting voter loyalty. Relying on O1G as a platform is neither strategic marketing nor effective brand building; it lacks vision and offers voters no compelling alternative.

By contrast, Fidesz combines emotional resonance with disciplined, multi-layered branding. Slogans like “Stop Brussels” and “Protect our families” are not only attention-grabbing, they are consistent, repeatable, and tied to a clear mission. The party amplifies these narratives across rallies, social media, and grassroots events, reinforcing identity, belonging, and long-term engagement. The opposition, in contrast, remains trapped in reactive protest: visible and viral, but fleeting and strategically hollow.

The lesson is clear: attention alone does not translate into influence or votes. To compete effectively, opposition parties must move beyond outrage-driven campaigns and memes, and instead develop a coherent brand strategy. This requires defining a unifying mission, crafting emotionally resonant narratives, and consistently communicating a vision that addresses voters’ core needs — Belonging, Security, and Control. Only by building a disciplined, authentic, and strategically designed political brand can the opposition transform short-term online engagement into lasting trust and electoral success, creating a credible alternative to Fidesz’s entrenched dominance.

Conclusion

Protest Might Win, But It Won’t Build

Let’s be honest: Hungarian politics has been a playground for propaganda for far too long.

Between 2010 and 2018, Fidesz–KDNP proved that disciplined, emotionally intelligent marketing could win hearts and minds. They built a brand, told a story, and created a sense of belonging. Then, somewhere along the way, the marketing compass broke. In the last two terms, exaggeration, fear, and top-down messaging crept in. Propaganda became the tool of choice. Fear replaced vision. Control replaced dialogue. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that this shift coincided with a slowdown in the country’s economic performance — when the underlying “product” falters, the messaging became louder, sharper, and more manipulative to compensate.

Meanwhile, the opposition has been living in propaganda’s shadow all along — reactive, clickbait-driven, outrage-based, and ever-chasing viral attention. O1G, memes, hashtags — they grab likes, but they don’t build trust. Even new voices like Péter Magyar, bright and visible, carry echoes of Fidesz’s inner circles and haven’t learned the craft of ethical persuasion. They are trapped in a loop: protest as performance, not as a pathway to lasting influence.

Here’s the contrarian truth: the path to real change is not louder shouting. It’s disciplined ethical marketing. And that comes with rules — the do’s and don’ts too often ignored:

Do use facts, not lies. Don’t distort reality.

Do respect opponents. Don’t dehumanize or scare-monger.

Do listen to all (!!!) voters. Don’t speak past them.

Do be transparent. Don’t hide your intent behind fake neutrality.

Do use emotion honestly. Don’t manipulate fear or hatred.

Do allow debate. Don’t silence dissent.

Do maintain ethical standards. Don’t cut corners.

Here’s the twist: if your strategy feels comfortable, you’re probably wrong.

Ethical marketing in Hungary will require imagination, courage, and a willingness to break the cycle of reactive outrage. Clicks, shares, and viral outrage will not build a movement. Vision, discipline, and ethical persuasion just might.

Sell what people feel they need, not just what they scream for online.

Belonging. Security. Control.

These aren’t slogans — they are the human drivers every strategist ignores at their peril.

Disagree? Good. I don’t write to be right — I write to be tested. Bring your “Tenth Man” perspective, your sharpest counterpoint, or even a quiet doubt — as long as it is supported by evidence and data. Sometimes the most useful critique is the one that unsettles my own thinking.

Don’t forget to subscribe for more Critical Hungary Insights!