Hungary’s Two-Speed Economy: Who Gains from the Forint—and Who Pays

Sovereignty, Strategy, or Structural Drift Behind the Euro Delay

Hungary’s delay in adopting the euro has created a two-tier economy—rewarding political elites, large exporters, and banks, while imposing rising costs on SMEs, households, and consumers. Framed as “sovereignty,” this policy increasingly functions as a mechanism to preserve the status quo rather than foster inclusive economic growth.

Hungary’s adoption of the euro has been postponed yet again—possibly until 2030 or later, according to Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. This raises a critical question:

Is the delay a deliberate strategy that benefits select groups, or a structural drift that harms the broader economy?

Part I: The Winners — Who Gains from Delay?

To understand who truly benefits from this policy choice, we must examine the economic architecture it supports.

This debate extends beyond monetary policy.

It’s about how Hungary’s economy is structured—and for whom. A careful look reveals two distinct tracks: a narrow elite reaping gains from the delay, and a much broader majority shouldering its costs.

Let’s make an attempt to sum up first the winners of the delay:

1. Political Power Structures and the Sovereignty Narrative

By keeping the forint, Hungary retains full control over monetary policy—setting interest rates, managing inflation, and guiding the exchange rate. This autonomy is framed as patriotic, with euro adoption portrayed as a surrender of sovereignty to Brussels. Orbán uses this narrative to bolster his nationalist stance.

Government-aligned voices present a weak forint not as a liability but as a strategic tool tailored to Hungary’s economic structure. It boosts export competitiveness, protects industrial jobs, and supports tourism by attracting foreign visitors—feeding both economic goals and nationalist messaging.

EU transfers in euros go further when converted into a weaker forint, allowing more domestic spending without raising taxes or borrowing. Mild inflation from currency weakening also reduces the real value of public debt, offering a quiet alternative to austerity.

Altogether, the forint underpins a broader message of strategic autonomy. Delaying euro adoption is framed not as reluctance, but as protection of national control. Yet a deeper question lingers: is this about national sovereignty—or shielding political elites from external oversight?

2. Large Exporters

Multinational and export-oriented firms in Hungary benefit from a weak forint: they earn in euros but pay costs in devalued forints, boosting profits. These companies dominate exports, with Hungarian SMEs accounting for just 12% of the share.

Even the Hungarian National Bank (MNB) admits devaluation helps exporters—though with diminishing long-term benefits. It offers short-term competitiveness, but fuels inflation and import price rises. This reinforces the government’s broader narrative of sovereignty, now translated into corporate profitability.

For major exporters, a weaker forint makes Hungarian goods cheaper abroad without cutting wages or margins—a key advantage in price-sensitive sectors like manufacturing.

Retaining the forint serves as industrial strategy. Euro adoption would remove exchange-rate flexibility that currently acts as an informal subsidy to exporters. Despite volatility, the system favors global competitiveness.

Exporters also benefit from EU funds—paid in euros but spent in forints—which stretch further and support state incentives, infrastructure, and subsidies, often in export-driven sectors. This happens without raising corporate taxes.

There’s a quiet fiscal bonus too: controlled inflation erodes public debt, stabilizing finances while avoiding unpopular austerity—favorable conditions for business.

So while the government pitches forint sovereignty as patriotism, exporters view it as leverage. The real question: is this sound strategy, or short-term advantage sustaining a system resistant to reform?

3. Commercial Banks and Currency Traders

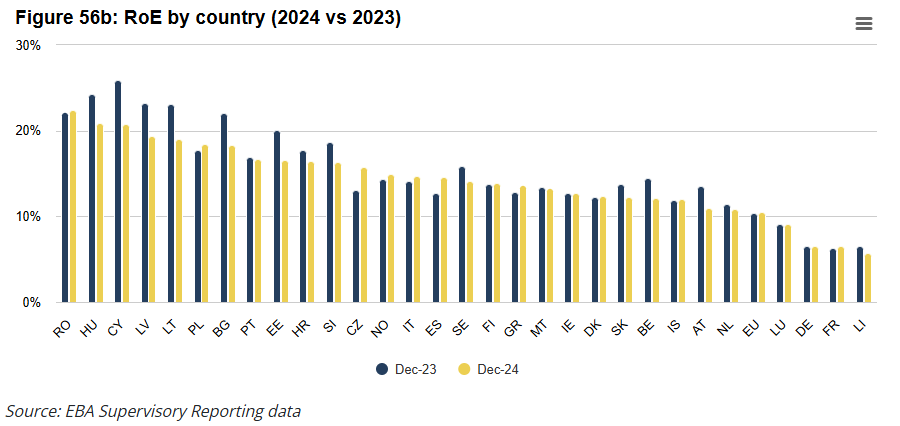

The chart below shows Return on Equity (RoE) by country in 2024 compared to 2023 (source: EBA). Hungarian banks report RoE figures that are double the EU average.

Hungary’s financial sector quietly benefits from its monetary sovereignty. The absence of the euro and continued use of the forint (HUF) provide key advantages:

Independent interest rate policy, supporting higher margins

Foreign exchange (FX) income from pricing, hedging, and transaction fees

Inflation-driven repricing of loans

Limited competition from eurozone-based banks

Opportunities in currency risk management

These dynamics mean that, beyond the real economy, the financial sector is especially well-positioned to capitalize on currency flexibility and volatility. Independent interest rate control allows banks to benefit from wider spreads and policy-driven liquidity, particularly during inflationary periods.

A depreciating forint inflates the value of foreign currency–denominated assets, enhancing bank balance sheets without real economic growth. At the same time, increased currency volatility fuels demand for FX services, hedging instruments, and foreign currency loans — all of which generate revenue for banks.

Inflation also reduces the real burden of public debt, enabling ongoing government spending without austerity. This indirectly supports domestic bond markets and overall banking activity.

The central bank’s flexible approach — blending monetary and fiscal tools — enables targeted lending programs and asset purchases that favor financial institutions. These measures would be subject to tighter constraints under eurozone rules.

In summary, Hungary’s current system does not merely serve political interests — it disproportionately benefits financial actors aligned with them.

4. The Hungarian National Bank (MNB)

The Hungarian National Bank (MNB) is a major beneficiary of the government’s decision to retain the forint. It gains full policy autonomy, allowing it to set interest rates, manage inflation, and intervene in markets without EU constraints. This flexibility aligns closely with government priorities and supports a politically controlled economic narrative.

A weaker forint also benefits the MNB’s own balance sheet. Euro-denominated reserves rise in forint value, often producing accounting profits that can fund state-aligned projects through opaque channels. Meanwhile, seigniorage income and asset purchases further expand its influence — beyond traditional monetary functions.

By staying outside the eurozone, the MNB avoids direct ECB oversight and maintains its institutional independence, which increasingly translates into political utility. It becomes not just a monetary authority, but a strategic actor in Hungary’s broader state-centric economic model.

However, another key question remains unanswered: how have these gains been used? Greater transparency from the MNB is needed, especially in light of revelations surrounding the ex-President of the MNB and the missing hundreds of billion HUF.

Part II: The Losers — Who Pays the Price?

But while these actors gain, others pay a quiet and compounding price—starting with the currency itself.

5. The National Currency (HUF)

Over the past decade, the Hungarian forint has been the weakest performer among regional currencies. Based on Eurostat data using a 2015 = 100 benchmark, the forint has consistently depreciated at a faster rate than the Czech koruna, Polish zloty, Romanian leu, and Bulgarian lev. (Click on the chart to view detailed currency performance.)

This pattern cannot be explained solely by market trends. It suggests intentional depreciation, possibly to sustain the short-term gains of the groups mentioned above.

A 27% depreciation of the forint over 10 years quietly transfers wealth from wage earners, savers, and consumers to exporters, the state, and financial institutions. While it boosts short-term competitiveness and fiscal space, the long-term tradeoff may be lower real incomes, inflation risk, and institutional dependency on a weak currency regime.

6. Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs)

Although SMEs make up 99% of Hungarian businesses and 95% are micro-enterprises, they contribute just over 12% to exports. Most operate domestically and cannot hedge against currency fluctuations (see chart Part II/1).

For these firms, the forint's volatility complicates planning, borrowing, and pricing. Unlike large exporters, they don’t benefit from the devaluation strategy. Sovereignty for the state becomes instability for the real economy.

7. Consumers and Households

Ordinary Hungarians bear the burden of inflation.

Imported inflation makes imports more expensive (e.g. energy, food, machinery, electronics, medicine). This fuels inflation, hurting consumers and reducing real wages. If combined with FX exposure, the impact on purchasing power is more significant. This reduces living standards, especially for the middle class.

Over two decades, Hungary has drifted further from the EU price stability norm. In 2004, inflation was 6.8%—already 2.7x the EU average. By 2023, it had reached 17%, still 2.6x the average, signaling persistent structural divergence. Many households have resorted to hoarding euros or comparing prices in foreign currencies to cope with volatility.

8. Long-Term Individual Investors

High inflation drives up interest rates. Hungary’s mortgage rates are among the highest in the EU, sometimes double those in eurozone countries. For households with modest incomes, reduces the share of disposable income available for saving and home ownership.

Compared to Belgium, Hungarian mortgages can be more than twice as expensive, despite much lower income levels. Is that a reward for staying out of the euro? Hardly.

9. Public Finances and Fiscal Credibility

Hungary consistently breaches the Maastricht convergence criteria:

Fiscal deficits exceed the 3% limit

Debt-to-GDP hovers around 74%, above the 60% threshold

These failures delay euro adoption, which in turn restricts access to EU stabilization mechanisms. The status quo encourages short-term fiscal populism over structural reform.

10. Public Trust and Sentiment

Public support for the euro remains high—above 75% according to Eurobarometer surveys. But mixed messages and endless delays have eroded confidence in the forint. Euroization of savings is a grassroots rejection of national monetary policy.

Part III: A Strategic Shift? Signs of Change

Even the MNB recently admitted the benefits of currency autonomy are diminishing. The competitiveness-through-devaluation playbook has reached its limits.

Meanwhile, the ECB’s 2024 Convergence Report ranked Hungary as one of the least prepared countries for euro entry, citing inflation, debt, fiscal deficit, and central bank independence as as ongoing challenges.

Part IV: A Path Forward for the Majority

If Hungary is serious about inclusive economic growth, euro adoption must be reframed—not as capitulation to Brussels, but as a commitment to stability, fairness, and opportunity.

Stability for SMEs and Families. Without currency stability, SMEs can’t plan or grow. Families can’t budget or invest. A timetable for joining ERM II would provide predictability and build trust.

Affordable Financing. Interest rates in Hungary must align with eurozone levels. Convergence can ease borrowing costs, fueling entrepreneurship and home ownership.

Targeted Support for SMEs. SMEs need more than macro stability. Accompany euro adoption with simplified taxation, access to euro loans, digital export tools, and procurement incentives.

Protection of Wages and Prices. Real wages are eroding. Inflation outpaces earnings. Eurozone membership offers greater price transparency and wage stability.

Conclusion: The Tenth Man Take

A government like Hungary’s gains fiscal and export advantages from a weaker forint, but at the cost of inflation, household pain, and long-term credibility. It’s often a political-economic balancing act — useful in the short term, risky in the long term.

As for why Hungary might intentionally delay euro adoption, there are some evident answers, such as:

To stimulate exports in the short term.

To fill budget gaps using higher forint-converted EU or export earnings.

To delay euro adoption, maintaining monetary policy autonomy.

To inflate away debt burdens or suppress real wages without explicit austerity.

But the real issue is that Hungary’s euro delay has created a two-speed economy. Large exporters, financial elites, and the state apparatus profit from currency autonomy. Meanwhile, SMEs, households, consumers, and everyday investors bear rising costs.

This is no longer a technical debate. It is a question of economic justice and long-term vision.

If Hungary truly wants to empower its people, it must stop treating euro adoption as a threat. It should become a central component of a transparent, inclusive national strategy.

The regional data already show the consequences of this divergence. Without reform, Hungary risks drifting another two decades—deepening inequality and sacrificing stability for the benefit of a few.

Disagree? Good. I don’t write to be right—I write to be tested. Bring your Tenth Man view, your sharpest counterpoint, or even a quiet doubt—so long as it builds on data. The most useful critique is often the one that unsettles my own thinking.

Don’t forget to subscribe for more Critical Hungary Insights!