Experienced, Educated, and Erased — No Country for Old Minds?

Bridging Yeats, HR, and blind spots in Hungary’s white-collar job market

Hungary’s labor market still shows a trend toward low-cost employment strategies. Most job listings prioritize minimal experience and require no higher education, with only a fraction targeting senior, qualified professionals. This suggests a lack of structural focus on valuing expertise and long-term human capital—raising concerns about the country’s ability to transition toward a knowledge-based economy.

Introduction: Setting the Paradox

In today’s Hungarian labor market—shaped by cost-saving pressures, wage constraints, and short-term priorities—experienced professionals with higher education may be finding fewer opportunities than expected. This seems puzzling at first, especially when dominant narratives repeatedly emphasize labor shortages.

Yet, when we examine actual job listings and hiring patterns, a contradiction emerges. If labor is in such short supply, why are skilled professionals overlooked? If talent is needed, why are experienced candidates treated as unaffordable? Are they erased form the listings?

This essay explores that paradox.

Drawing on a snapshot from one major Hungarian job platform—while not fully representative, still revealing—it suggests that the issue lies not in ideological bias, but in deeper structural choices. These patterns point to a labor market built on low value-added models and rigid cost containment, where experience and qualifications are not just undervalued—but seen as unaffordable.

Literary Echoes: No Country for “Old” Minds

Taking inspiration from W. B. Yeats’s line no country for old men, this piece asks: in an economy that prioritizes cheap labor over deep knowledge, is there still room for experience, expertise, and “unageing intellect”?

Yeats’s famous verse from Sailing to Byzantium paints a vivid contrast between youthful immediacy and the neglected wisdom of age:

“Caught in that sensual music all neglect / Monuments of unageing intellect.”

This lament over the marginalization of knowledge and experience is echoed a century later in Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men, adapted by the Coen brothers. Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, bewildered by the moral disarray of the modern world, struggles to find his place in a system he no longer understands.

What the Data Tells Us

To explore the above question, a basic descriptive analysis was conducted using publicly available job listing data from profession.hu, Hungary’s market-leading job portal.1

According to the site, 55% of suitable candidates apply through the platform. It receives the highest thematic job traffic in Hungary and had over 1.4 million registered users by Q2 2024.

The platform typically hosts 10,000–15,000 active job listings at any given time—a significant enough dataset to draw directional insights.

A quick breakdown by education level reveals:

76% of job listings do not require higher education.

Only 24% explicitly request a college or university degree.

Breaking the data down by experience level:

72% of listings require less than 3 years of experience.

Only 0.4% of postings seek candidates with 10+ years of experience.

In comparison—and to underscore just how strikingly low the demand for experienced professionals is—assuming a roughly 10,000-sized random sample, the margin of error at a 90% confidence level is approximately ±0.82%. Yet, if we take the full set of job listings on Profession.hu as our sample and focus only on those requiring 10+ years of experience, they account for just 0.4% of all listings—well below the margin of error itself. This is not just statistically negligible; it’s an alarming signal about the structural priorities of the labor market.

Cross-tabulating both filters (higher education and 10+ years of experience) yields just 27 listings in total—or less than 0.3% of all postings

No Country for Experienced Professionals?

This data raises pressing questions:

Is this simply a feature of profession.hu’s user base and listing profile?

Is it influenced by tax policies, such as the under-25s income tax exemption, pushing employers toward younger hires?

Or is it a sign of a structurally imbalanced labor market, skewed toward low-cost, low-complexity jobs with limited space for knowledge-based roles?

“Whatever is begotten, born, and dies… Caught in that sensual music all neglect / Monuments of unageing intellect.” —W. B. Yeats

In this context, the well-educated professional with a decade or more of experience begins to resemble Yeats’s "old man"—not necessarily aged, but sidelined. Not because their skills are obsolete, but because they are seen as expensive, incompatible with short-term cost logic.

The Narrative Gap

Some of the HR narratives from mainstream media continue to sound the alarm about labor shortages. Statements like "Many industries are experiencing a labor shortage" or Jooble’s “Sectors Facing the Most Severe Labor Shortages in 2025” are common.

In Profession.hu’s, an HR survey dedicated to the job market, "HR Körkép 2024 Q2" report, employers cite their top three recruitment challenges as:

Poor candidate quality

High salary expectations

Low applicant numbers

But when compared with the actual content of job listings, a clear paradox emerges.

Companies report that they cannot find applicants—yet job ads overwhelmingly avoid targeting experienced professionals. High salary expectations are cited as a barrier—but little evidence shows a willingness to invest in long-term human capital. And the low applicant number claims, seem to support the labor shortage narrative

To translate these employer concerns into plain terms: there is a shortage of low-experience, less-educated, and inexpensive labor—precisely the segment most employers are targeting.

Is this the companies’ fault? Not entirely.

It’s the symptom of a dysfunctional system—one that over-relies on low value-added labor, caters to cost-focused investors, and keeps wages artificially low to maintain a “competitiveness gap” with regional peers.

Yeats, Sheriff Bell, and the Hungarian Job Market

Since the early 1990s, successive Hungarian governments have pursued a strategy focused on attracting foreign capital—often at considerable cost. This has included the privatization of national assets, generous subsidies for foreign investors (ranging from 15 to 30 million HUF per job), and the construction of an economy heavily reliant on manufacturing.

Critics have long described this model as an “assembly-line economy,” while officials counter with claims that Hungary is becoming a hub for “high-tech industry”

The outcome?

Official statistics do show an increase in R&D jobs. However, due to the underlying manufacturing logic, the majority of newly created positions are blue-collar, low experience and low-wage.

This is further evidenced by indirect government communication about jobs that the domestic workforce is increasingly unwilling or unable to fill—particularly those that are physically demanding or low-paid. In response, Hungary has increasingly turned to guest workers, with conflicting estimates ranging from 100,000 to several hundred thousand brought in from distant countries to keep production lines running.

The job market data supports the critics' view of an 'assembly line economy' more than the official narrative of a 'high-tech industry', since based on the local job supply, the need to underpaid, lower educated workforce seemingly is higher, while the need to skilled, educated and experienced workforce seems very small.

If the economy would be indeed a high tech one, that would be reflected in wages and labor costs too. However, this is not reflected in actual wage and labor cost data neither.

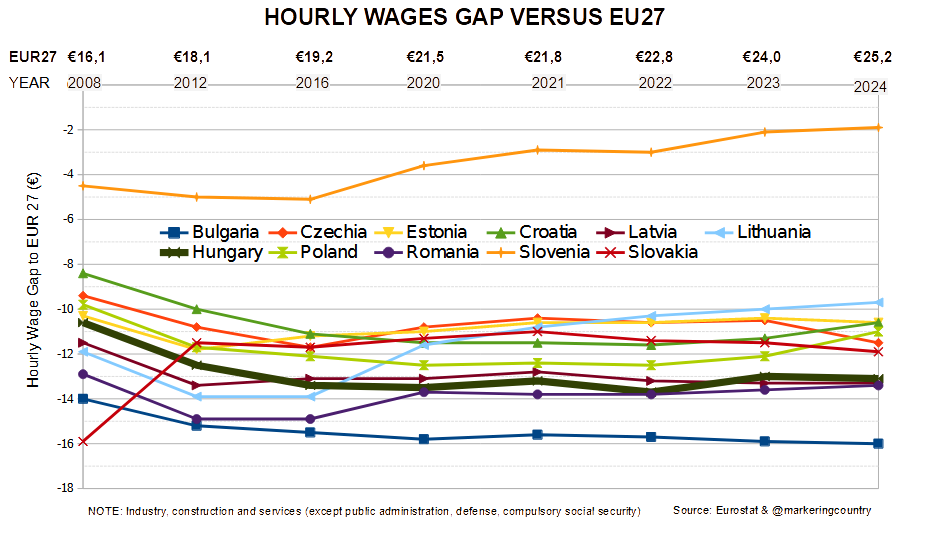

Another great indicator is to check the Eurostat market data on industry, construction and services hourly wages (by excluding the public administration, defense, compulsory social security wages which are state controlled) and benchmark this toward the European Union 27 (EU27) market average hourly wages.

In a regional context, when compared with 11 other Central and Eastern European markets (Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, and Slovakia), Hungary shows no indication of catching up with the EU average hourly wage trend over the 2008–2024 period. In contrast, since 2016, both Slovenia and Lithuania are consistently closing the gap, while since 2022, Croatia and Poland are showning similar tendencies. The remaining countries do not display such convergence.

According to the data, in 2008, Hungary’s average hourly wage lagged the EU27 average by €10.1. By 2012, the gap had widened to €12.5, and as of 2024, it stands at €13.1. Since 2012, the gap has fluctuated within a narrow range of €13.0–€13.7. Hungary currently has the third-largest wage gap relative to the EU27 average, with only Romania and Latvia showing only slightly larger discrepancies. Was thjs stagnation most likely a strategic decision aimed at maintaining cost competitiveness within the region or not? )see Appendix, Chart 1).

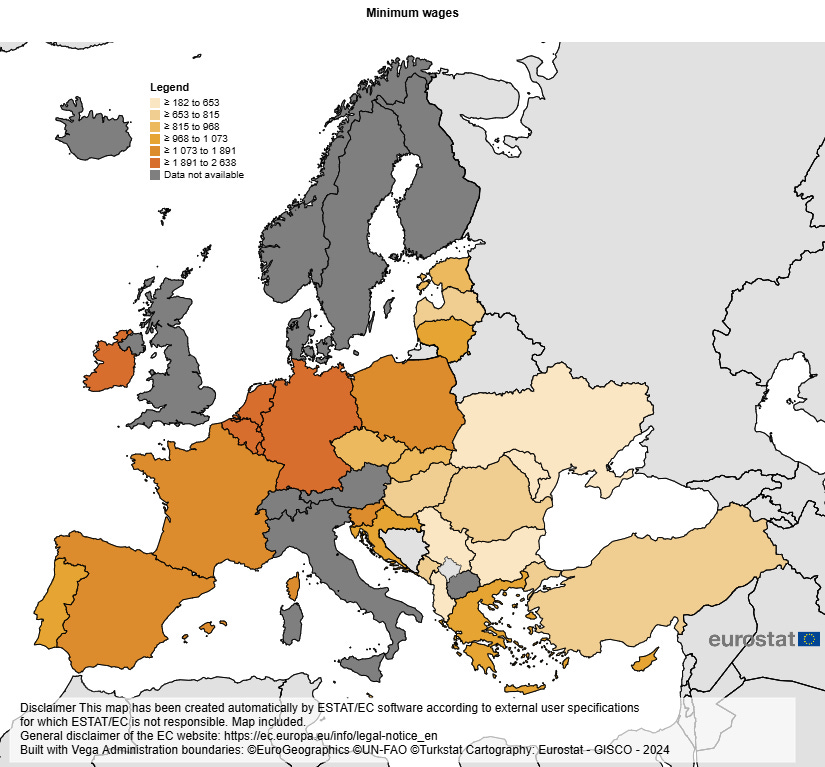

Last but not least, Hungary ranks second-lowest in the EU for minimum wages, just above Bulgaria. (see Appendix, Chart 2). This is another supporting argument to the low cost direction.

One might ask: has anything really changed in the last hundred years for "old minds"? The Hungarian white-collar job market suggests perhaps not—or is it pointing to something else entirely?

Contrarian Conclusion: Patterns, Not Absolutes

The data presented here offers only a snapshot and does not capture the full complexity of Hungary’s labor dynamics. But it does reveal structural patterns worth questioning.

The striking underrepresentation of experienced, highly educated professionals in job listings may not stem from active exclusion—but from economic forces: cost-efficiency, industrial bias, tax incentives, and labor market models built for volume, not value.

This is not a moral failure—it is a systemic one.

Still, the consequences are stark. A labor market that undervalues those with the ability to lead, train, and innovate—those who know not just how to operate within the system, but how to improve it—is not positioning itself for long-term resilience.

Final Reflection: No Country for Old “Minds”

Yeats’s lament over the neglect of “monuments of unageing intellect” feels eerily relevant today. Hungary’s labor market model—built on short-term cost control rather than knowledge creation—is becoming, in effect, no country for old “minds.”

With over 90% of jobs requiring less than five years of experience and 71% requiring no higher education, the data points unmistakably to a low value-added economic model—an 'assembly-line economy,' as some critics describe it.

It may serve immediate investor interests. But in doing so, it risks wasting one of Hungary’s most valuable and underused assets: experienced, educated professionals with the insight to create lasting value.

The question remains—not as rhetoric, but as an urgent policy challenge:

Is there still a place in this economy for those who know the system—not just how to work within it, but how to improve it?

A recalibration is needed—not just to absorb experience, but to leverage it in shaping a smarter, more sustainable labor model.

Appendix:

Chart 1: Hourly Wages Gap versus European Union 2008-2024 (source: Eurostat).

Chart 2: Comparison of Minimum Wages in European Union 2025 S1 (source: Eurostat).

Disagree? Good. I don’t write to be right—I write to be tested. Bring your Tenth Man view, your sharpest counterpoint, or even a quiet doubt—so long as it builds on data. The most useful critique is often the one that unsettles my own thinking.

Subscribe for more Critical Hungary Insights—where uncomfortable data meets uncomfortable questions.

Disclaimer: Profession.hu was contacted for confirmation regarding the information cited from their portal; however, no response was received by the time of publication. Therefore, the information presented here reflects the publicly available claims listed on their website at the time of writing. Specifically:

Profession.hu states it is the market-leading job portal in Hungary based on data from a survey of 1,000 individuals aged 18–59, conducted in Q2 2025.

According to Similarweb traffic data, Profession.hu was the most visited thematic job portal in Hungary in Q1 2025.

Based on a survey of 500 individuals aged 16–59, Profession.hu claims to be the best-known job portal in Hungary in Q1 2025.

The claim that 55% of suitable candidates apply through Profession.hu is based on 2024 Mystery Shopping research, where candidate suitability was determined by independent recruitment experts assessing resumes against job criteria.

The statement that 7 out of 10 positions are filled through Profession.hu is based on monthly research titled by LeadGeneration Kft.

This disclaimer aims to clarify that while the above data and claims are sourced directly from Profession.hu, they remain unverified by direct correspondence.