Hungary’s housing market breaks the mold: with 91% ownership, low mobility, and minimal reliance on agents, what looks like inefficiency elsewhere functions here as a survival strategy. Bricks and mortar remain the only reliable safety net in a volatile economy. Government policy, however, runs against this logic—pouring subsidies into new, unaffordable builds that prop up developers and a narrow band of buyers. With so few new units and transactions, these programs cannot reshape the market; they only expose how housing policy serves industries more than households.

Hungary’s real estate market runs on a set of unwritten rules— that are rarely questioned, yet deserve much closer scrutiny.

Beneath the surface, the housing market is full of peculiarities that raise more questions than answers.

Let’s break it down.

Hungarian Real Estate Market Oddities Explained

To understand the unique character of Hungary’s real estate market, a few key features stand out.

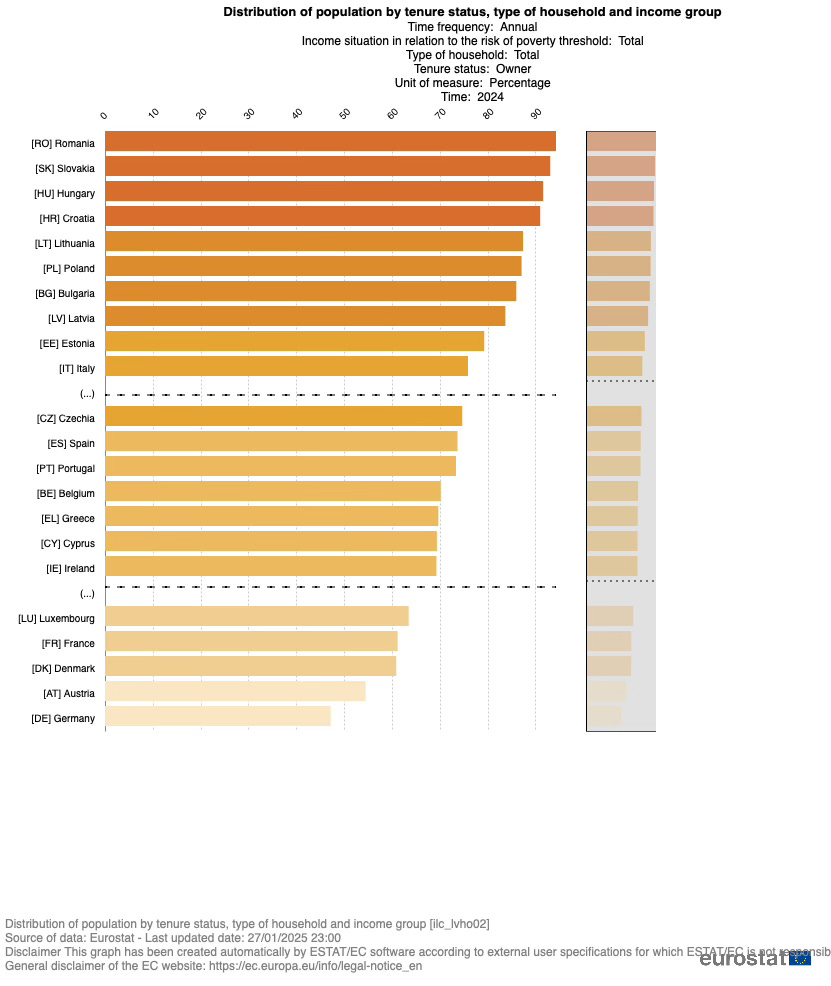

Ownership: First, home ownership is exceptionally high—over 91%—a figure far above the EU average. This stems from a mix of historical, cultural, and economic factors.

During socialism, private property was restricted, but the transition of the 1990s saw a wave of privatisations, with apartments and houses sold off at very low prices. This allowed many families to secure ownership cheaply. At the same time, Hungary developed only a weak rental market: institutional investment in housing remained minimal, tenant protections limited, and renting widely seen as unstable and unattractive.

Culturally, ownership became deeply associated with security, family continuity, and social status. Intergenerational transfers—parents helping children buy or inherit property—further reinforced the cycle. The result is a system where owning a home is the rule, not the exception.

Housing stock: According to the Hungarian Central Statistical Office, Hungary’s housing stock stood at 4.616 million units as of January 1, 2025.

Since 2007 the yearly average housing stock increase was approximately 20k units. The average value is heavily skewed by the FX denominated mortgage loans period between 2007-2011 (see more related information in The Hungarian Mortgage Propaganda essay). However when comparing the 2025 January 1st data with 2024 same data, the increase was only approximately 12k unit.

Based on real estate transaction data, the overall transaction rate in 2024 was 2.5%. Applying this rate to the current housing stock translates into just over 115,000 transactions across the country in 2024.

At this level of ownership, though, the deeper question is whether such low growth is really a “problem” at all—or rather a sign of saturation, where the market has simply run out of new buyers and new demand. In other words, Hungary may not be building too little housing—it may already be as owned-out as a country can get… or is there still room for genuine organic growth?

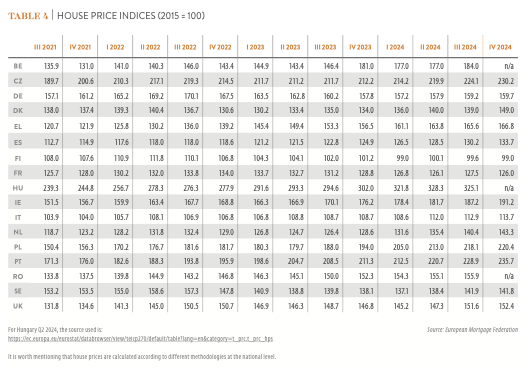

Real estate pricing: If we take 2015 as a baseline, real estate prices in Hungary had surged by 325.1% by Q3 2024—a staggering increase compared to an inflation index of around 165% over the same period.

Looking at the shorter horizon, the three-year growth rate exceeded 35%, only slightly below the cumulative inflation rate of just over 39%. Still, it’s important to note that much of this growth was built on a relatively low starting base when compared with other European housing markets.

Currently the national average sqm prices are at slightly higher than €2.000, while average asking price is around cc. €180.000. While in Budapest the average sqm prices are higher than €3.450 based on koltozzbe.hu statistics. You are going to have a significant variation in the prices in different geographical regions or locations.

But this raises an uncomfortable question: is this price surge truly organic growth, or something else? Are we seeing genuine demand and purchasing power at work—or are prices inflated by speculative buying, distorted credit policies, or the lack of viable investment alternatives in Hungary’s economy? In other words, is the housing market reflecting real value, or is it simply the byproduct of a system where money has few other places to go?

Real estate brokerage paradox: Another striking oddity of Hungary’s housing market is the role—or rather, the lack of role—played by real estate agents.

In most mature housing markets, agents are central intermediaries. They handle 50–70% of transactions, professionalize the process, and shape public perceptions of value. In Hungary, the picture is radically different.

According to the Hungarian National Bank’s 2023 Housing Market Report, only 10.6%–13.1% of transactions involve agents. That means that out of roughly 115,000 housing deals a year, barely 12,000–16,000 pass through an agent at all. Yet an estimated 8,000–10,000 agents (or more) compete for this sliver of the market.

The math is brutal: on average, each agent closes fewer than two transactions per year. Which raises the obvious question: how can there be so many agents for so little business?

Unless, of course, the numbers don’t capture the full picture. Is the data misleading, incomplete—or is the Hungarian real estate profession built on something other than actual transactions?

Rethinking Hungary’s Housing Market

Step back, and the numbers tell a story almost the opposite of what conventional wisdom suggests. Commentators like to describe Hungary’s housing market as “underdeveloped” compared to Western Europe: weak rental markets, low agent penetration, uneven regional pricing. But what if those so-called shortcomings aren’t flaws at all? What if they are deliberate adaptations—features that make sense in a country shaped by volatility, inflation, and mistrust of institutions?

Take the home-ownership rate of more than 91%. From a Western perspective, it looks like an imbalance: proof of a broken rental sector and lack of institutional capital. But from inside Hungary, it can just as easily be read as a rational hedge against uncertainty. When inflation, currency swings, and political shocks have repeatedly wiped out savings, property becomes the default insurance policy. It may not be efficient, but it is resilient.

Or consider prices. A 325% surge since 2015 screams “bubble” to outside observers. Yet Hungary’s market started from a historically depressed base. Even now, at around €2,000 per square meter nationally and €3,450 in Budapest, Hungary is still far cheaper than most European capitals. The surprise isn’t how high prices have climbed, but how long they lagged behind.

Then there’s mobility. Barely 115,000 housing transactions take place each year in a country of nearly 10 million. By most standards, that looks like market stagnation. But again, what if low churn isn’t failure but design? In a society where homes are inherited, passed within families, and tied to identity, stability—not liquidity—is the point.

Seen this way, Hungary’s housing market isn’t broken. It’s operating under its own set of rules. History, culture, and deep distrust of intermediaries have created a system that looks strange only if you expect it to behave like Germany, France, or the Netherlands. Property here is not primarily an asset class; it’s a survival strategy.

But resilience comes with contradictions. The same features that protect households expose the flaws in government policy. If nine in ten Hungarians already own their homes, what exactly is being solved by subsidies1 for new construction? Are these programs designed to improve affordability, or to manufacture demand for the construction industry? With less than 2.5% of the housing stock changing hands each year and fewer than 15,000 new units built annually, can subsidies move the needle at all—or are they little more than symbolic politics?

The bigger challenge is not quantity but quality: modernising Hungary’s vast existing stock with insulation, energy upgrades, and basic liveability improvements. Why should taxpayers underwrite new-build buyers—often middle- or upper-class families—while millions remain in outdated housing? Is it constitutional to subsidies with taxpayer money certain preferential segments? If the real goal is family welfare and population stability, wouldn’t deep modernisation subsidies deliver more by cutting bills and raising living standards for everyone?

Which leads to a sharper suspicion. Housing subsidies may not be about households at all. They may be about channeling resources toward politically connected developers.

Hungary’s housing story, then, is both one of survival and of distortion: a system that protects households in spite of volatility, but where policy increasingly seems designed to protect industries instead.

Disagree? Good. I don’t write to be right—I write to be tested. Bring your “Tenth Man” view, your sharpest counterpoint, or even a quiet doubt. Sometimes the most useful critique is the one that unsettles my own thinking.

Don’t forget to subscribe for more Critical Hungary Insights!

Over the past ten years, Hungarian government has pursued an unusually interventionist housing policy, tying subsidies closely to family policy and demographic goals. Examples of major schemes :

Interest-subsidized housing loans and fixed-rate schemes

In addition to CSOK, Hungary has introduced preferential housing loans with capped interest rates, especially for first-time buyers. For example, in 2024–2025 the government announced a new 3% fixed-rate housing loanavailable to first-time homeowners, supplementing the CSOK framework.

CSOK – Családi Otthonteremtési Kedvezmény (“Family Home Creation Benefit”)

Launched in 2015, CSOK has become the flagship housing support program. Families with children (or even those committing to have children) receive non-refundable state grants and access to subsidized housing loans to buy, build, or renovate homes. The subsidy scales with the number of children and whether the property is new or used. CSOK has been repeatedly expanded, but always tied to family size and demographic incentives.